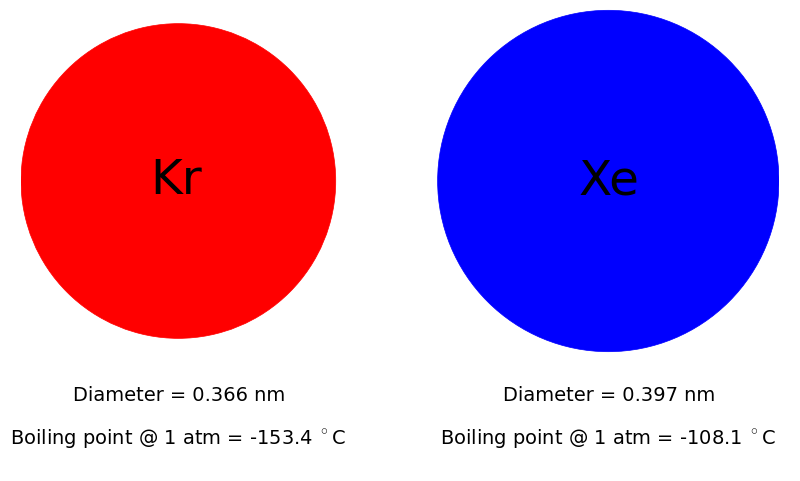

The noble gases xenon (Xe) and krypton (Kr) have several applications. Xenon is used as an anesthetic and for imaging in the health industry and as a satellite propellant in the space industry. Both xenon and krypton are used in lighting, in lasers, in double glazing for heat-insulated windows, and as carrier gases in analytical chemistry.

Xenon and krypton are expensive because of their scarcity and difficulty to produce. Krypton and xenon are present in Earth’s atmosphere at concentrations of 1.14 and 0.087 ppm, respectively. The conventional method to obtain pure xenon and pure krypton is as a byproduct of the cryogenic distillation of air to obtain oxygen and nitrogen; the byproduct stream is a mixture of 20 mol% Xe and 80 mol% Kr. At Air Liquide, this stream is compressed to 200 bar, stored in cylinders, and shipped to a separate Xe/Kr separation plant to undergo another cryogenic distillation to separate this Xe/Kr mixture.

Separating the Xe/Kr mixture by distillation at such low temperatures is very energy- and capital-intensive. Experiments have shown that an adsorption-based separation using porous materials at room temperature is a promising, less energy-demanding alternative to separate the Xe/Kr mixture. The idea behind an adsorption-based separation is for one gas species in the mixture to preferentially adsorb in the material, leaving the other gas species behind in the gas phase. When the material is saturated, we can then heat it to drive off the adsorbed gas, regenerating the material for another cycle.

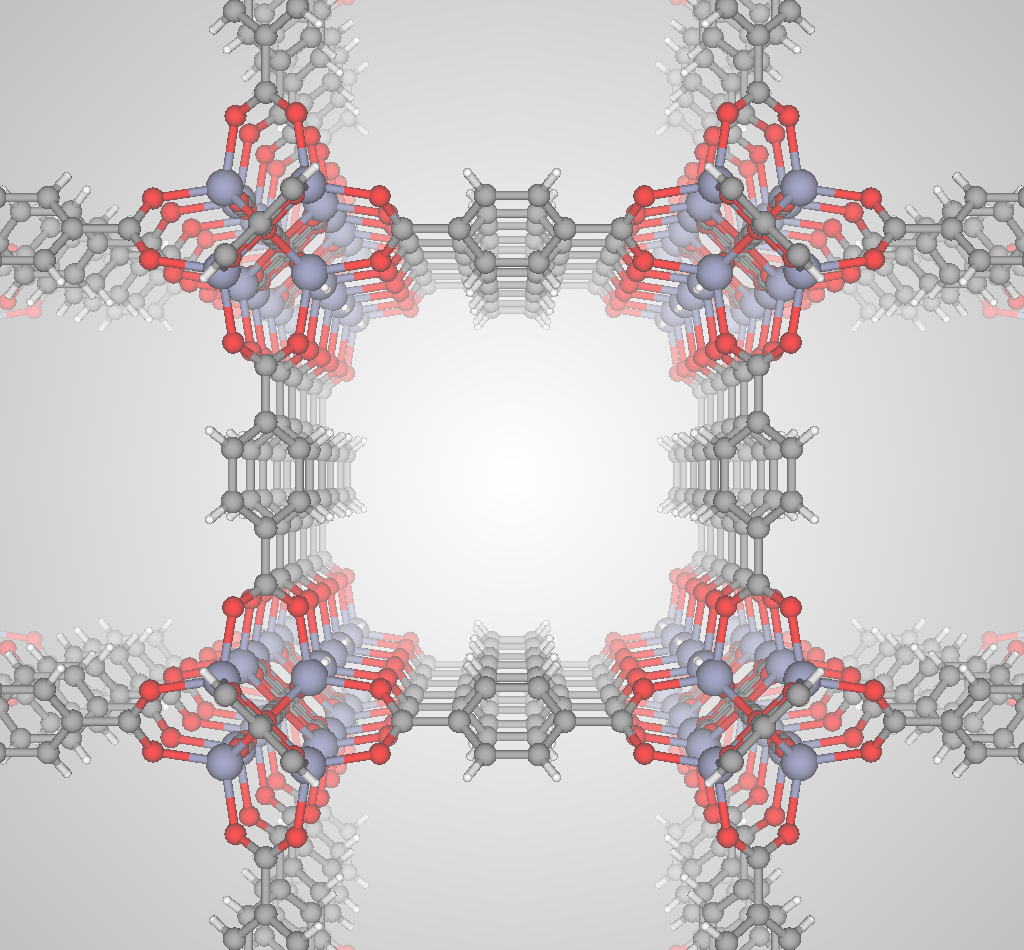

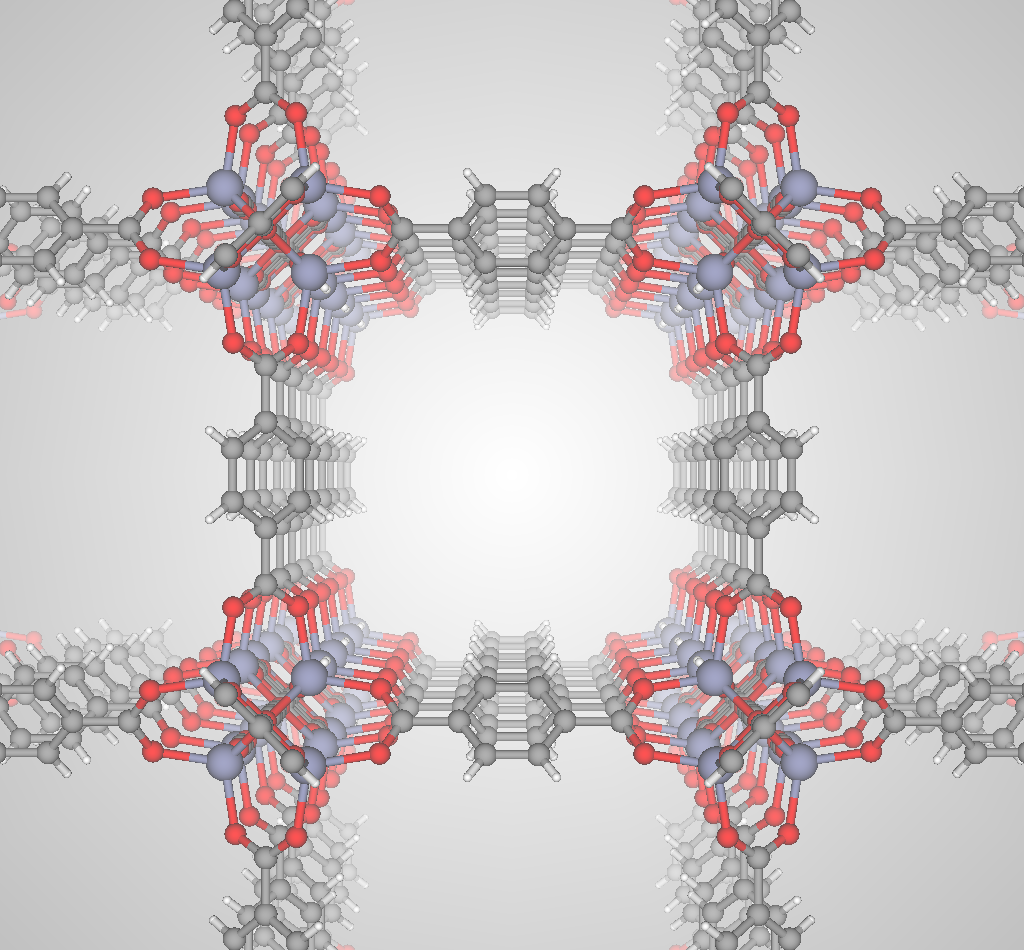

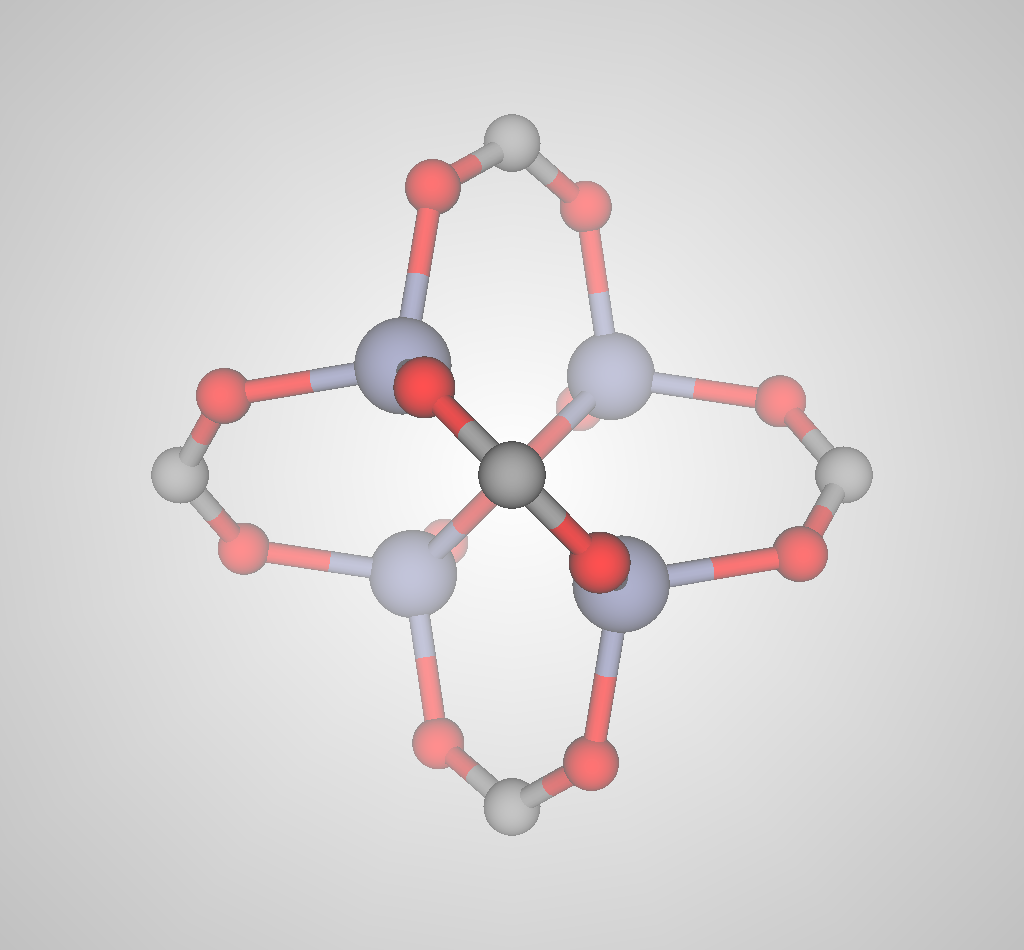

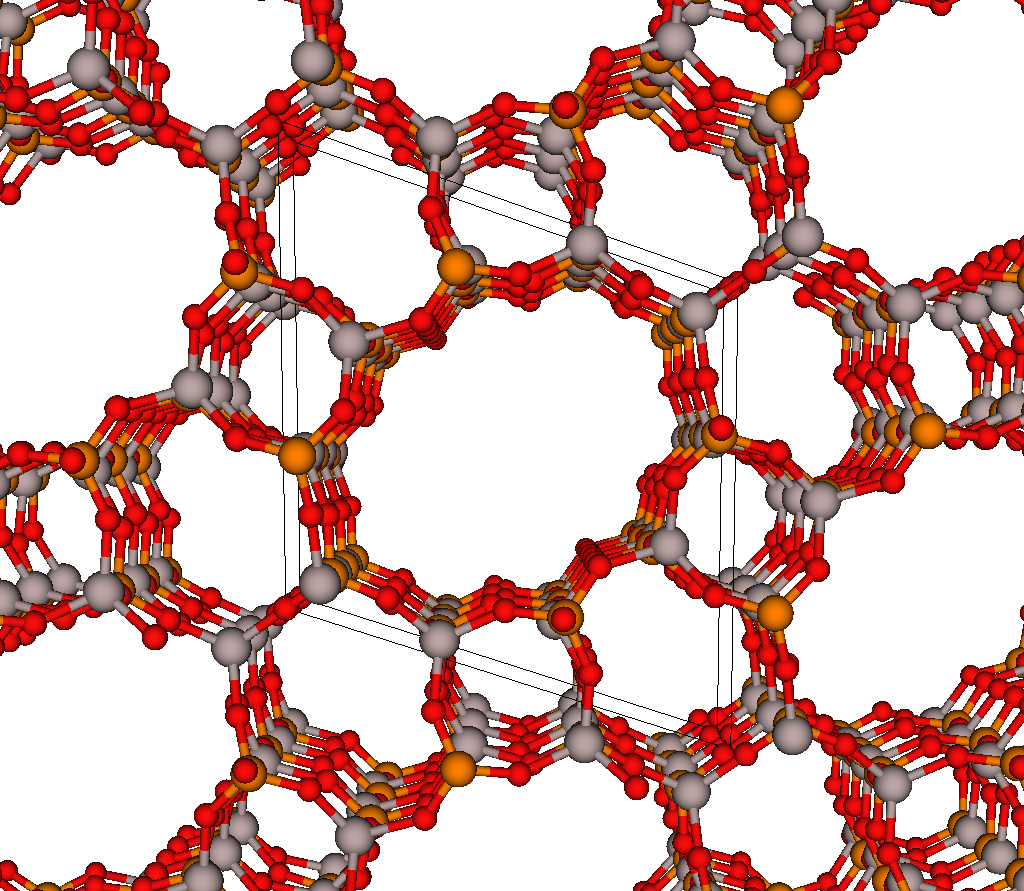

The most selective materials are nanoporous materials, which have nano-sized pores so that just a few molecules can fit inside. Fig 2 shows an example nanoporous material, IRMOF-1. A single gram of nanoporous material can have as much internal surface area as a football field! Xenon and krypton are recruited into the material because of van der Waals interactions with the walls of the nanopores; because xenon has a larger electron cloud than krypton, we expect most materials to prefer xenon. Some materials are reverse selective; these have pores that are too small for and thus exclude xenon but are large enough to accommodate krypton.

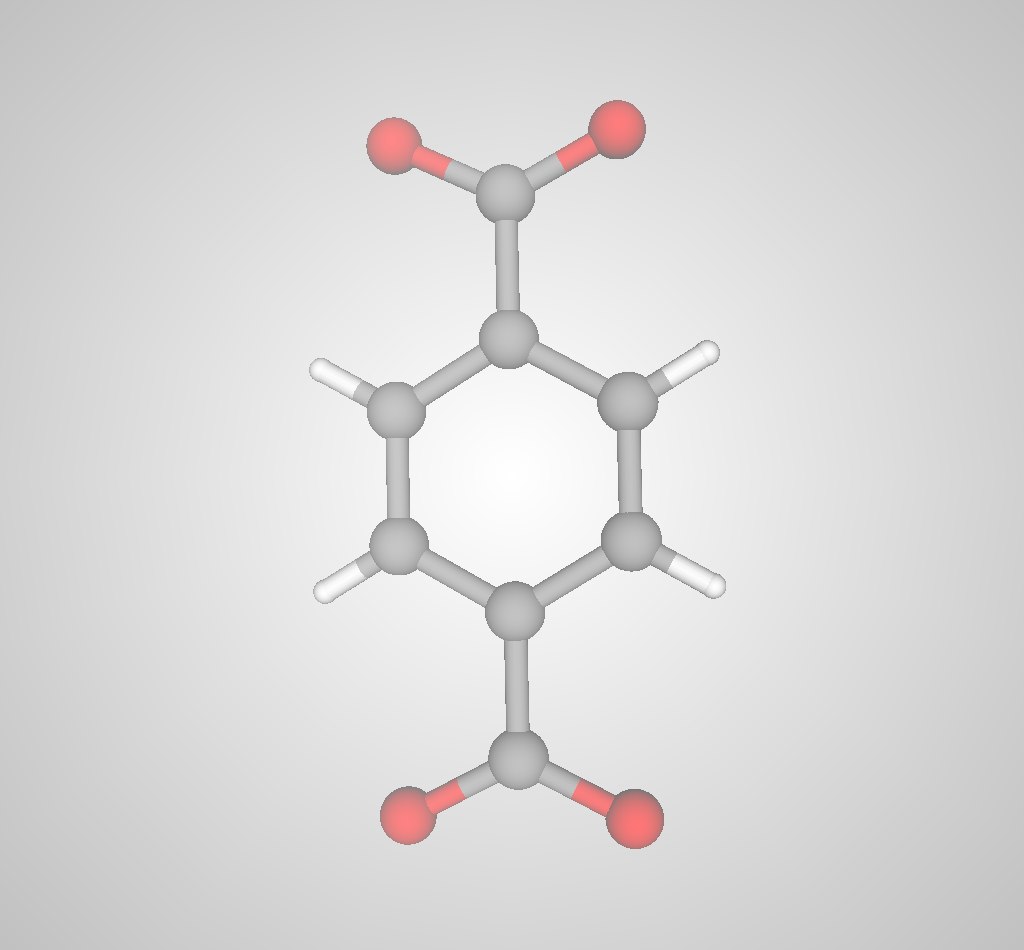

Advanced nanoporous materials are highly tunable. For example, consider metal-organic frameworks (MOFs). MOFs are synthesized by combining organic molecules called linkers with metals or metal clusters that serve as nodes; the linkers and metal nodes self-assemble to form a 3D coordination network. For example, the linker and metal node used to synthesize IRMOF-1 are shown in Fig 3.

(a)

(a)

(b)

(b)

By changing the linker and metal node in MOFs, one can in principle synthesize an unlimited number of different materials. To date, over 10,000 different MOFs have been synthesized in the lab!

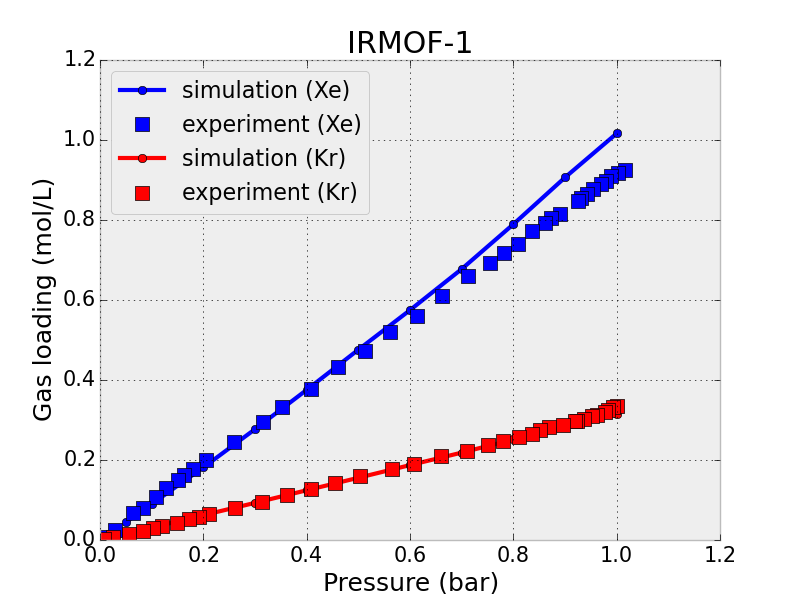

This tunable chemistry leaves us with many options of nanoporous materials to synthesize and test for Xe/Kr separations. Because of limited resources and time, synthesizing all of these materials in the lab and measuring their Xe/Kr adsorption is infeasible. A much faster and cost-effective route to materials testing is to use molecular simulations to predict what materials will be the most selective for xenon. For example, Fig 4 shows the simulated xenon and krypton adsorption isotherms (how much gas is adsorbed at different pressures) in IRMOF-1, which agree well with the experimentally measured isotherms.

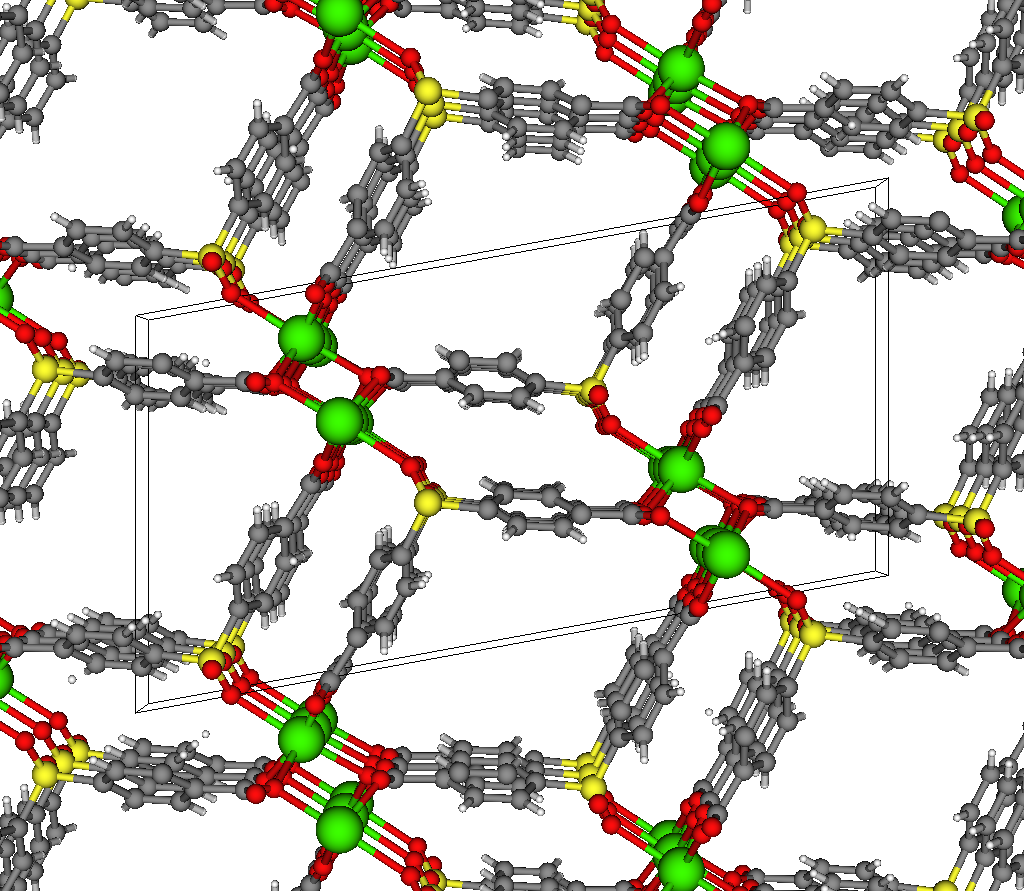

In our article in Chemistry of Materials, we used mathematical models, molecular simulations, and machine learning to identify the best materials for Xe/Kr separations out of a database of over 600,000 nanoporous materials.

With such a large number of materials, the computational resources required to simulate Xe/Kr adsorption in each material become prohibitive. To expedite our computational testing of the entire database, we turned to an algorithm used in artificial intelligence, a random forest. A notable example of the success of random forests is the Kinect for Microsoft’s video game console, XBox. From a real-time video feed of your body, the XBox Kinect detects and labels your body parts in real-time so that your body movements can control the character in the video game. For the Kinect, a random forest was shown hundreds of thousands of examples of people in different positions, and it learned to recognize body parts from these training images. Analogously, we trained a random forest to recognize high-performing materials for Xe/Kr separations by showing it examples of high- and poor-performing materials for Xe/Kr separations.

Molecular simulations are computationally expensive. By using a random forest, we needed to simulate Xe/Kr adsorption in only a relatively small training set of materials. We then showed the remaining materials to the random forest to predict their separation performance. The time to train the random forest and show the remaining materials to the random forest is insignificant compared to the time we would have needed to simulate Xe/Kr adsorption in all of the materials by brute force. Thus, utilizing random forests allowed us to screen the entire database of over half a million materials in a reasonable time.

The most lucid result of our study is a list of top candidates for Xe/Kr separations. The two most selective materials in the database are a MOF and aluminophosphate zeolite analogue, both of which have already been synthesized but not yet tested for Xe/Kr separations. We hope our computational study will incite the characterization of the top materials that we identified.

(a)

(a)

(b)

(b)

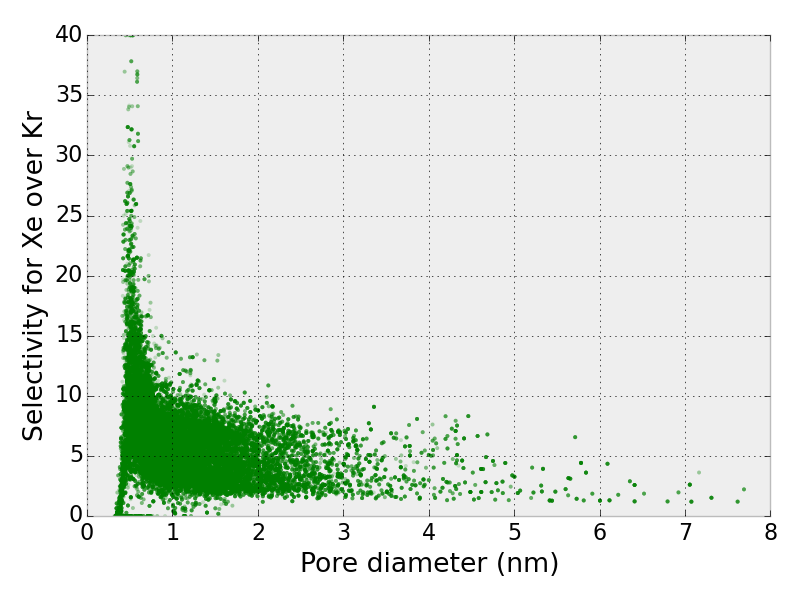

With the large volume of data that we generated, we can identify data-driven guidelines for synthesizing a good material for Xe/Kr separations. For example, if we look at the relationship between the selectivity for Xe and pore size, we see that materials with large pores have small selectivities. The most selective materials have a pore size of ~0.45 nanometers, but this pore size does not guarantee a good material; other variables are at play.

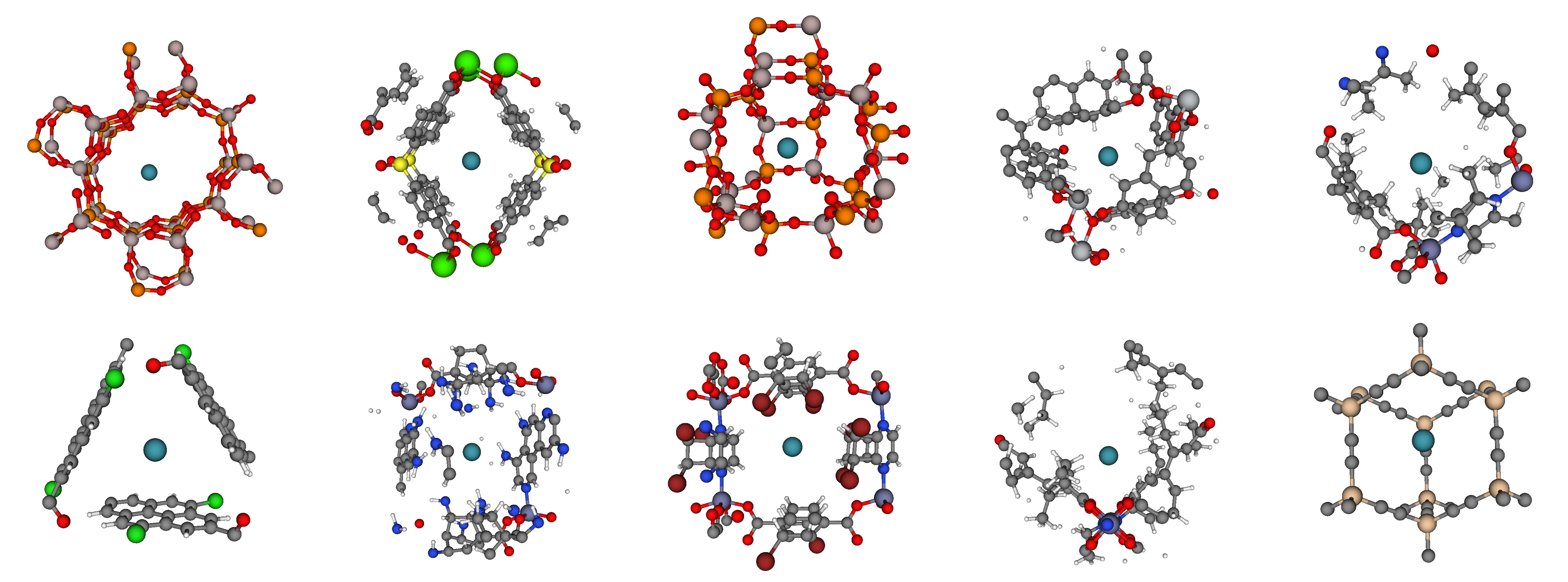

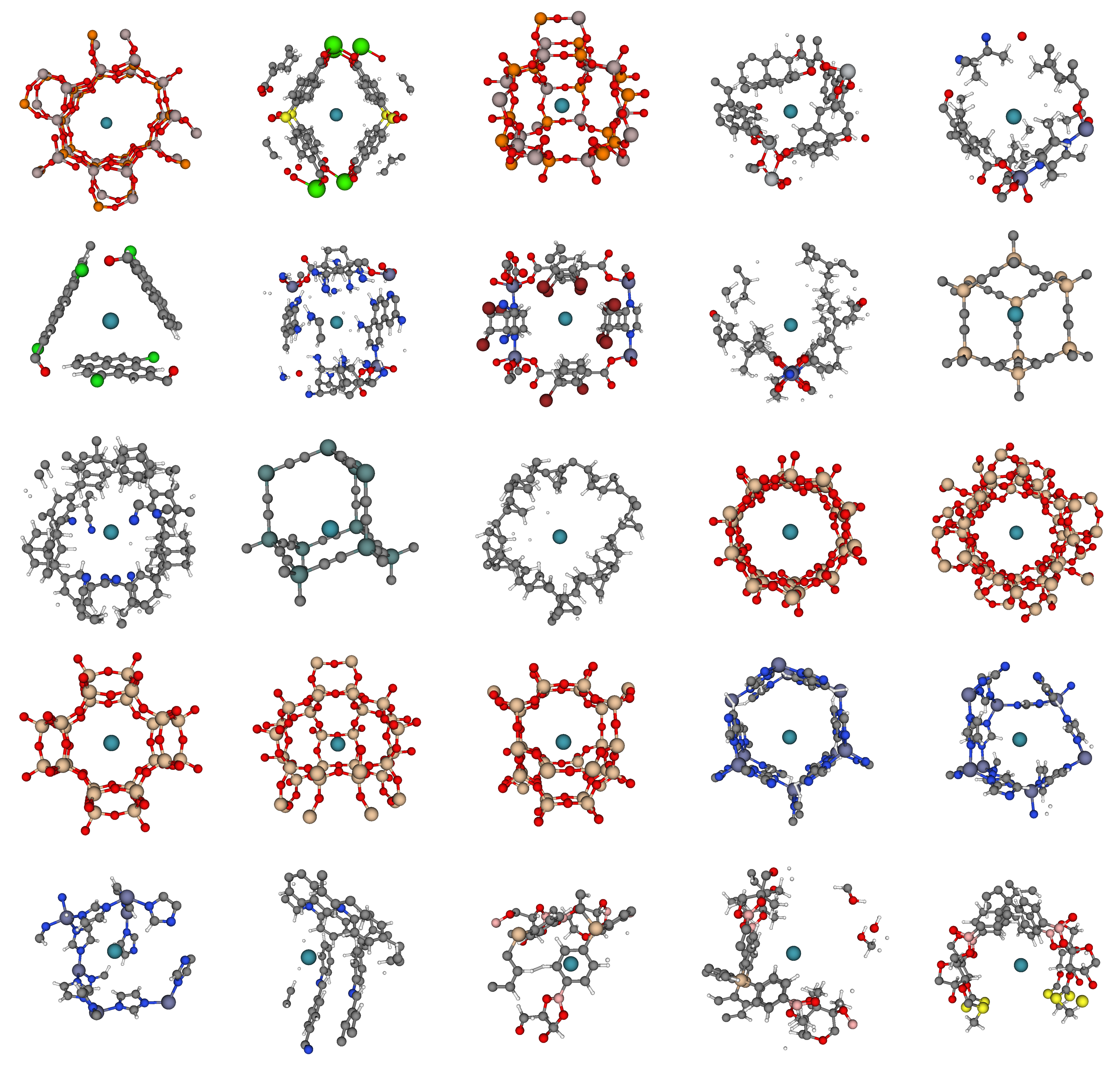

We took a look at the binding sites in the most selective materials. The most selective binding sites exhibit a striking diversity of geometries: tubes, pockets, cages, and rings of chemical moieties can form a binding site. Fig 7 displays the binding sites in the most selective materials, with a xenon atom (teal) at its minimum energy position inside the pore.

The diversity of these binding sites and the lack of a simple, obvious design rule for synthesizing a good material for Xe/Kr separations underscores the importance of using computer simulations to screen these databases of materials, focusing experimental efforts on the most promising materials rather than relying on a trial-and-error approach in the laboratory.

Nanoporous materials have several other potential applications, such as natural gas and hydrogen storage, carbon capture, chemical sensors, drug delivery, and catalysis. For each of these applications, computer simulations can be used to screen these databases of materials to focus experimental efforts on the top candidates and elucidate design rules.

Reference: C. Simon, R. Mercado, S. Schnell, B. Smit, M. Haranczyk. “What are the best materials to separate a Xe/Kr mixture?” Chemistry of Materials. (2015) Link

comments powered by Disqus